WHAT IT REALLY MEANS TO BE A KAMBO PRACTITIONER

Today, anyone can call themselves a Kambo practitioner.

Kambo sticks are sold online. Information on the topic is widely available on social media. Ceremonies take place in city apartments, retreat centers, and even gyms. There are individuals calling themselves “master” practitioners and jungle tourists claiming shamanic lineage after a brief visit to the rainforest.

But here’s the truth: the title “Kambo Practitioner” means absolutely nothing on its own.

What truly matters is who the person is, how they work, why they do it, and how much they genuinely understand, not just about the medicine, but also about people, the body, safety, and how to hold space for transformation. Being a Kambo practitioner is not a badge, not a role to play, and certainly not something to feel special about. It is a responsibility, one that is often underestimated.

To truly understand what it means to serve this medicine, we must look deeply into the evolution of the modern Kambo practitioner, a journey that spans from the depths of the jungle to today’s urban landscapes, from ancestral wisdom to current confusion.

The Traditional Roots of Kambo

This sacred frog secretion originates from the Amazon rainforest and is still used today by a few tribes: the Matsés, Katukina, Kaxinawá, Yawanawá, and the lesser-known Amahuaca. There is evidence that other tribes once used Kambo, but many have abandoned their traditional practices or no longer exist. This fate nearly befell the Yawanawá tribe as well.

Like many Indigenous groups, the Yawanawá were targeted by Christian missionaries, who actively suppressed native rituals, sacred chants, and the use of plant and frog medicines. Ceremonial life was banned, and shamanic knowledge was condemned as demonic. Entire generations were raised without access to their spiritual and medicinal heritage.

By the early 2000s, Yawanawá traditions were on the verge of extinction.

Fortunately, a revival began. Tribal leaders consciously chose to reclaim their ancestral wisdom, with crucial support from the neighboring Katukina, who had preserved much of their medicine work, especially with Ayahuasca and Kambo. What is now often seen as “traditional Yawanawá” practice is actually a syncretic blend: part cultural memory, part Katukina tradition, and part innovation shaped by modern realities.

It’s difficult to say how much of this knowledge would have survived without this revival. Many younger tribe members had distanced themselves from their traditions, driven by modernization and the desire to fit into a rapidly changing world. In many ways, the damage was caused by foreign influence, but ironically, it was also preserved thanks to foreigners who took an interest in these traditional medicines.

Today, the practice has experienced a renaissance. For many native people, it has become a sustainable business model. They are no longer forced to seek employment outside their communities, and instead can fully dedicate themselves to preserving and cultivating their traditions.

For them, Kambo is not a trend. It’s not a detox. It’s not even just a medicine. It is a spiritual, energetic, and practical tool for survival, used to remove “panema” (bad energy, bad luck, or laziness), enhance hunting skills, and increase vitality.

It’s important to understand that while there are similarities in how Kambo is used among tribes, there are also distinct differences. For example, among the Matsés, Kambo is not limited to shamans as it often is in other tribal traditions connected to Ayahuasca. Any tribe member may apply it to themselves or others. Often, the strongest, most hardworking, and respected hunters take on this role. It’s a communal, intuitive practice, guided by experience and a belief in energy transmission. Women are also involved in harvesting and applying Kambo, though traditionally within defined gender roles.

In contrast, tribes like the Katukina view Kambo as part of a formal shamanic path. Traditionally, only initiated men and those well respected administer the medicine, often accompanied by chants or as part of broader spiritual rituals and shamanic dietas. There are also specific rules about which parts of the body may be used for application. The approach is differently structured with a strong shamanic core.

Kambo’s Journey Out of the Jungle

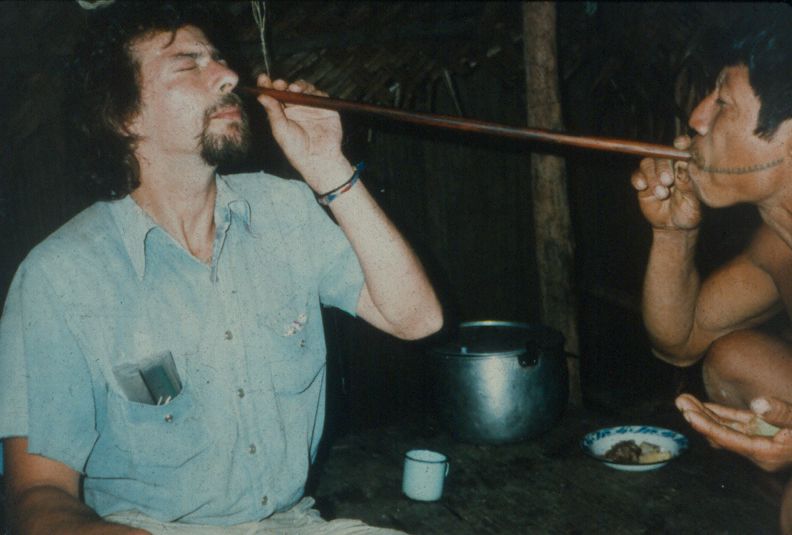

The first written account of Kambo comes from 1925, by French missionary Constantin Tastevin, who lived with the Kaxinawá. But it wasn’t until the 1980s that it caught Western attention, thanks to journalist Peter Gorman. After receiving Kambo from the Matsés, he published his experience and brought samples back for scientific study, helping to spark its popularity.

As Ayahuasca ceremonies spread across the globe in the 1990s and early 2000s, Kambo quietly followed. Travelers began bringing Kambo sticks home and experimenting on themselves and others.

Some of these early adopters began offering sessions and promoting their services online, becoming the first modern “Kambo practitioners” as we understand the term today.

As more people experienced the power of Kambo, others felt called to learn how to serve it. This led to the organic emergence of the first Kambo training programs. Today, thousands have gone through such trainings, and countless more have received the medicine. Some programs are deep and well-guided. Others are shallow, misleading, or even dangerous.

The Problem with the Modern Kambo World

Let’s be honest. There are beautiful, grounded, highly skilled Kambo practitioners out there helping people. But there is also a lot of confusion, danger, and ego in the modern Kambo scene.

Over the past two decades, a wide range of styles and ideas have emerged. Some practitioners strictly follow a specific tribal tradition. Others build on it, incorporating new techniques. And some have completely distanced themselves from tradition altogether, inventing entirely new ways of practicing. While experimentation can sometimes lead to innovation, it can also cause harm.

For example, traditional views on pre-session fluid intake vary, some tribe memebrs drink nothing, others about a liter. But some modern practitioners have encouraged excessive amounts of water, leading to hyponatremia, hospitalization, or even death. Most experienced practitioners today agree that 1.5 to 2 liters is safe for most people but sadly, not everyone has gotten that message.

Just because some individuals can handle large doses doesn’t mean everyone will react the same. We’ve seen the danger of improper dosing, yet some practitioners continue to ignore the risks.

Some protocols push for multiple sessions in a short time. This can be more profitable for the practitioner, but it’s often done without properly assessing the client’s state or needs.

Hosting large indoor circles without enough bathrooms or trained support staff can lead to unsafe, overwhelming experiences for participants.

There are also people pretending to be shamans, acting with overconfidence or dishonesty. In tribal communities, everyone knows each other. In our modern world, it’s much easier to fake expertise. This applies to practitioners and even trainers some of whom may live in the jungle. Simply being born there, or visiting once, does not make someone a shaman or healer.

And yet despite all this people are still drawn to Kambo. Because it helps. It is powerful, cleansing, and transformative. But when misused, it can also be traumatic, harmful, or even fatal.

Why Traditional Knowledge Alone May Not Be Enough

After reading all of this, one might conclude that working only with traditional practitioners is the safest option.

Historically, there are no known cases of natives being harmed by Kambo. But we must understand why that is. Tribal communities are small sometimes just a few hundred to a few thousand people. A native practitioner may have only ever applied Kambo to a few hundred individuals in their lifetime, all with similar diets, lifestyles, and strong physical health. There may be even genetic and generational tolerance to the secretion.

But that’s changed. Today, many tribal practitioners apply Kambo to foreigners with vastly different backgrounds. This doesn’t mean no harm has occurred. Nor does it mean every native has pure intentions.

This is not to diminish the depth of traditional knowledge. Rather, it is to acknowledge the reality of today, modern clients are not tribal members and not every native is a skilled practitioner or has pure intentions.

Today many people that seek Kambo sessions often have chronic conditions. Take medications. Eat processed foods. Live sedentary lives. Carry emotional trauma. Some have fragile mental health or heart conditions.

The risks are different. The needs are different. And so, the responsibilities of the practitioner must also be different.

Tradition gives us roots. It teaches us about the spiritual dimensions of this work. But modern practice demands discernment, adaptation, and ongoing learning.

What should a Modern Kambo Practitioner be able to do?

Before the Session

• Take a detailed medical intake (medications, heart issues, mental health, etc.)

• Screen for contraindications

• Discuss the client’s intentions and needs

• Provide clear preparation instructions

• Educate the client on what to expect

During the Session

• Create a safe, calm, clean, and private environment

• Choose appropriate placement and dosage based on sensitivity and needs

• Offer physical, energetic, spiritual and emotional support

• Know when to stop, or remove the medicine

• Be trained in first aid

• Remain fully present, grounded, and sober

After the Session

• Offer integration support if needed

• Provide dietary and recovery guidelines

• Be available for follow-up questions or concerns

Ongoing Responsibilities

• Understand human physiology

• Have a strong spiritual praxis

• Continue learning from elders, peers, and science

• Never fake shamanism or make false promises

• Reflect regularly on one’s own intentions and integrity

• Serve from humility—not performance

Being a Kambo Practitioner with integrity

A real Kambo practitioner should know: this is not about them. It’s about the person in front of them and the sacred medicine in their hands.

All tribes agree there’s something to the energetic transmission between practitioner and receiver. For that reason, a Kambo practitioner must work on themselves continually, striving to be a vessel of purity and positive energy.

If you’re seeking to receive Kambo or to become a practitioner don’t be seduced by feathers, flashy social media ads, or shiny certificates. Anyone can get those.

Serving Kambo isn’t about burning skin and applying medicine. That part is simple. Even a monkey could learn that.

To be a true practitioner, you must be committed to self-work, guided by high ethics, and deeply motivated to help others. It’s not a title. It’s a path. And only your actions from the heart will show who you really are.